Blog

Sea Note 1: Cosmos in a Cup

- By Ann Charity Weaver

- •

- 31 May, 2020

- •

Sea Note 1

Picture Caption. Local bottlenose dolphins Cosmos (on right) and Prism (on left) take a mobile nap. Cosmos is missing the tip of its dorsal fin, compliments of a small shark. The neat little amputation removed all of the marks that could be used to identify the dolphin except a tiny square notch low on its fin.

By now, most of us have experience wearing a mask into sparsely-populated public places and veering away from other masked patrons to maintain the recommended social distance. It can be unsettling to be veered away from because it creates the creepy feeling that one is contagious.

I saw a clerk in a local shipping shop literally recoil from an unmasked patron and brusquely demand that he back away from her several feet, a dance they danced as they thrust paperwork at each other involved in sending the patron’s fax. One feels sure that the patron will find another shipping shop whose clerk does not make him feel as if he were visibly crawling with cooties.

Masks hide vital social information. One might see another patron’s eyes crinkle in a smile, but the smile itself is hidden. From what I have seen, masks make it easier for some people to be rude or, at a minimum, dismissive.

Masking one’s identity happens at sea among our local dolphins too. In an interesting twist, it was the lack of change from friendly behavior that recently provided clues about the identity of a mysterious “masked” dolphin.

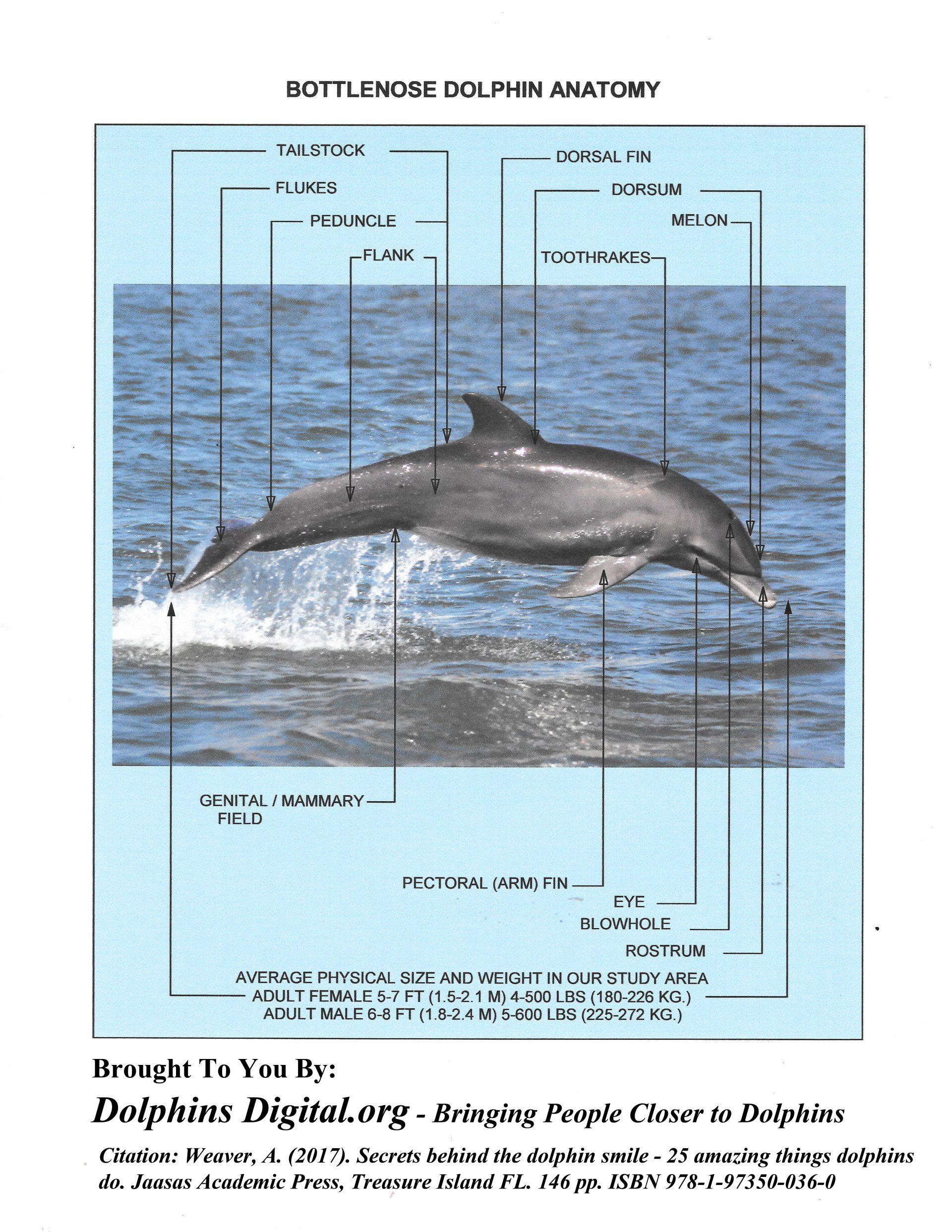

Capt. John Heidemann and I study local dolphins under federal permit. We tell dolphins apart by unique patterns on the fin that sits on their backs like a sail, their dorsal fin. Though made of tough cartilage, the dorsal fin becomes ripped and otherwise scarred over time because the dolphin uses it as a sword, shield, and chew toy. Most of the resulting tatter patterns are subtle, a little nick here, a little notch there. Tatter patterns on males tend to be more conspicuous and change more over time because males engage in more rough-and-tumble exchanges than females do.

However, all dolphins run the risk of tangling with a shark. Even a light chomp from a shark can disfigure a dolphin’s previous pattern. Disfigurement of the dorsal fin can mask the dolphin’s identity to observers like me. Lack of recognition is partly because familiar tatters are gone and partly because I recognize tatter patterns holistically. Thus, somewhat like wearing a mask, losing part of the pattern can obliterate the dolphin’s identity for me in the field. However, back at the lab, I am able to search my photo archives to see if any remains of the previous pattern match one of the 418 dolphins in our photo-identification catalog.

As masks were becoming mandatory on land, Capt. John and I came across a trio of teen dolphins in early spring. Two were known to us, Prism and Yukon. Both were males born in 2016 and newly-weaned from their mother’s care by the age of 4 years. Prism had tangled with a small shark in 2017, known in our house as the Year of the Snappish Shark for the unusual outbreak of dolphins with fresh shark bites that summer. In Prism’s case, his shark scars make him easy to recognize. Yukon sustained a wound the following year, though not clearly from a shark.

The third teen in the trio had also tangled with a small shark that amputated the top of its dorsal fin. We did not recognize this dorsal fin pattern. There were two possibilities. One was that the dolphin was new to us, such as a friend the boys brought to town from Egmont or Clearwater. The other possibility was that the dolphin was not new to us but that the shark bit off its identifying tatters, making it a mysterious “masked” dolphin.

My only clue to its identity was a tiny square notch where the skin was missing low on its dorsal fin. Because it represented mystery, I called the “masked” dolphin Cosmos in honor of astronomer Carl Sagan.

At first the teen trio was sleepy. This allowed Capt. John to glide our boat smoothly alongside them at close range. For many minutes I greedily collected high-quality photos to study later for more clues to Cosmos’ identity.

About the time we spied new dolphins in the distance ahead, the trio quickened and headed over. Soon the seas sizzled with a half dozen teens embroiled in riotous exchange. They thundered around the seas as twos or threes, rearing up and swimming over each other to playfully sink a schoolmate or rolling on their sides, pectoral fins waving like small flags at political rallies. Bright white bellies glared briefly against pale green waters. It was a good-natured wrestling match, sea style.

The mysterious “masked” dolphin Cosmos swam round and round the wrestlers. It appeared to be playing as hard as the others to the casual observer. But it was not, unless dancing on the side of a whirling merry-go-round is the same as riding it. This behavior was a clue that Cosmos was familiar with the other teens, all of whom were males, but was a female because teen females in our local waters tend to behave like this.

There was another possible clue about the “masked” dolphin’s identity from its behavior. Cosmos stuck close to Yukon. Yukon’s mother is Yami. Yami visits our local waters occasionally and swims with X when she does. X had a calf in 2015 we call Xenios, Greek for hospitable. From the few observations of these two dolphin moms and their calves over the last four years, we knew that Yukon and Xenios knew each other since they were babies.

Back at the lab, close inspection of the day’s photos of Cosmos revealed that the tiny square notch of skin missing from its fin was the only physical clue to its identity. I opened my photo-identification catalog and headed straight for Xenios.

Ahha! The mysterious “masked” dolphin Cosmos was no more. Unmasked at last, Cosmos was Xenios! Now, tell us about that shark…

Share

Picture Caption. Free-ranging bottlenose dolphin Queen P’s life is threatened by a brutal bite on the head from a large peevish shark.

Many thanks to Dr. Ann Pabst and Dr. Bill McLellan in the Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, for providing expert anatomical details of P’s shark bite and likely prognosis.

I have heard of potholes in the road of life. But this was a crater. Just two days ago, we found her shortly after the shark bit her brutally. I have been haunted since. Queen P is such a cool dolphin.

We met P in 2003. We simply called her P because that was where we were in the alphabet, labeling each dolphin with a letter as a gender-free name. To me, gender-free names are essential because male and female bottlenose dolphins swimming past one’s boat look the same at first. Gender-neutral names avoid the confusion of misunderstanding a dolphin’s gender and misinterpreting its behavior as a result.

One exception is an adult seen consistently with a baby. The adult is presumably the calf’s mother and is therefore presumably female; however, this too is occasionally misleading. P had a little baby with her two years later. We called him “PC” for P’s Calf. He successfully weaned from his mother’s care at the unheard-of early age of 16 months.

Over time, P evolved into “Queen P” because she handled her affairs with a certain maritime majesty. For example, she was comfortable around our research boat from the start. Most of the dolphins took about two years to become used to our hovering presence and frank interest in their activities (the process called habituation). Not P. She maintained her cool by going about her dolphin business undeterred by our presence from the start. Only one other dolphin out of 200 had that level of confidence besides P.

I remember when P took it step further and started to acknowledge us. It was the mellow morning when my assistant Marie and I found her in the back of a small cove having breakfast. We slowly approached until we were 2-3 boat lengths away (about 40-60 feet or 12-18 meters) and clicked the throttle into neutral gear to watch her from a distance. P swam over to us directly and did a high jump next to the boat. Pivoting elegantly in mid-air, she dove back in cleanly with barely a splash and resumed her search for breakfast. Her high jump, known as a bow, was one of my early introductions to the fact that wild bottlenose dolphins greet individuals in their social circles somewhat like humans do.

Queen P took it even further with her staggering revelation about the mental lives of wild dolphins: She dropped her son PC off at our boat for us to babysit. It was a cool and colorful autumn afternoon. PC was about a year old. Capt. John and I were motoring slowly through the narrow opening of the hidden cove at the north end of our study area. P and PC swam past amid red and orange leaves dotting green water.

PC paused to play a game with Catch with himself. His “ball” was a horsetail, a mangrove seed that looks like a curved brown pencil. He tossed and caught his toy again and again. Thrilled to see this wild game so close, I videotaped him eagerly.

Meanwhile, Queen P kept going until she reached the other side of the hidden cove. We kept an eye on her as a small dark dot in the shimmering blue distance.

PC played Catch near the boat for many minutes. Time moves at a different pace at sea than it does on land. But when I am watching dolphins, time slows until it seems to stop. However, I record time as part of the data and knew that PC played at our boat until P returned 19 minutes later. We watched her nonchalant return. PC dropped his toy, went over to her, and fell into step. They left the hidden cove side by side.

Capt. John and I grinned at each other in disbelief. Had we just babysat a young wild dolphin at his mother’s request?! Considering the understanding and trust required between parent and babysitter, this was one of many humbling observations that earned Queen P her royal moniker.

How Queen P communicated to PC to stay at our boat until her return remains a fascinating mystery.

For years, Queen P stayed scar-free. This is easier for females than males but a tricky task for any naked animal living among razor-sharp oyster shells and schoolmates who grab each other with mouths lined with sharp teeth. P’s scar-free state was another testimony to her regal ways among other dolphins, inspiring me to write about it in an admiring article called Perfect P and Classic Q (see Behavior Articles 1-100 on this site, article # 97).

Like any intelligent being, Queen P has her attitudes. She is no model dolphin, no unthinking obedience hanging around our boat. For example, for some years in the middle of our study, she evolved from Queen P to “P the Putz” because of her fleet resistance to close observation. Granted, several dolphins have gone through “rejection” periods in which our drawing close for observation became difficult. I find the ability to develop “an attitude” to be a compelling reflection of dolphin social psychology. Unbound by pool walls and owing us nothing, they are free to express their thoughts about being studied, and everything else, which I savor. For some years, P allowed herself to be studied, then did not allow herself to be studied. Then her attitude changed when again she allowed herself to be studied.

Queen P reminds me to respect the dolphins as intelligent, thinking individuals with their own personality and views. Behaviors like changes in attitude over time suggest that bottlenose dolphins are even more cogent and conscious than science has shown them to be in the lab. This idea makes me feel even more humble and appreciative that they allow me to peer into their private lives at all.

The crater that battered Queen P’s road of life took the form of a large peevish shark that reared up over her head on the 18th of September 2020 and, biting down with power, gouged it deeply. Her skull is exposed. The shark could have easily left behind a few souvenir teeth imbedded in her bright sassy capable brain. It could have damaged her blowhole.

Dear P, your prognosis is poor.

Follow-up Facts

In my book Secrets behind the Dolphin Smile – 25 Amazing Things Dolphins Do, Queen P stars in the chapter, Mystery at MacDonald’s; plays a vital role in the chapter, The Princess and the Pea; appears in the chapter, Dying for Attention; and swims through the chapter, How a Dolphin Might Launch a Conversation.

In my book, Why Dolphins Jump – A Picture Book of the Acrobats of the Sea , Queen P or her calves are featured on pages 17-18 (Bow: Attract Attention), page 42 in Picture 51, pages 51-52 on how to remove a remora, page 61 (Leap: Seeking Attention), page 87 in Picture 107, and page 127 (Surfing: Waiting for Disney).

Dedicated to Sharon Plotkin, a crime scene investigator in southern Florida, to help energize her recovery from back surgery.

It was a steamy summer day in Florida that started too slowly to imagine that it would ever lead to driving energy.

Blue skies were dotted with fluffy clouds wrenched free of the thick air. The heat upon us like a shawl, Capt. John and I rocked on swaying green seas and watched a mother dolphin with her four-year-old son. The seas were soft and only 7 feet deep, but hot: 89° F (32° C). No one moves much in that kind of heat.

We named the mother dolphin Stick for the game of Catch she played with a stick when we first met her 17 years ago as a young calf still in her mother’s care. We named her son Stem as a play on words.

Stem devoted several minutes to herding small fish into his mouth by spinning around them. He spun in a maneuver called a pinwheel. This effortless twirl probably perplexes the fish because, from its perspective, the pinwheeling dolphin suddenly surrounds it - for that last moment before it is swallowed into eternity.

While Stem hunted, his mom Stick wandered around nearby in behavior called meandering travel. She swam very slowly. She barely cleared the surface to breathe. Both behaviors are typical of dolphins made sluggish by August’s warm seas. But they are also typical of expectant mother dolphins close to delivery.

When sated, Stem cruised over and threaded behind our boat. Perceiving the little dolphin’s behavior as a bid to surf, Capt. John accelerated steadily so the dolphins could catch a carnival ride if they chose.

Stem seized the moment. He barreled into the wake, sliding down sea water stretched like clear taffy between theatrical leaps that created sudden gray silhouettes against white froth.

By and by, Stick materialized alongside Stem. As seen in the videos that accompany this Sea Note, they prodded each other as they surfed, the exquisite dolphin control belying any proposal that they stumbled against each other accidentally.

After several minutes of sliding across the seas at a blistering 10 miles per hour, Stick and Stem were suddenly joined by a third dolphin. Big, beefy, and a bit beat up, it had managed to catch up as our boat sped by. Now three dolphins surfed shoulder to shoulder, the suddenness of their switch from sluggish to speedy an illustration of the bottlenose dolphin “psychology of spontaneity.”

Surfing dolphins are exhilarating to watch. Yet this surfing saga told a deeper tale. Young Stem is afflicted with the mysterious condition that periodically sends him into spasms. As in a seizure, he loses his ability to swim smoothly, instead pouncing awkwardly toward the surface to breathe and pitching sideways because he cannot regain his balance. In the worst episodes, the poor little guy swims on his side in a helpless circle. The seizure passes in time and his behavior returns to normal.

Seizures peppered his first year of life but stopped occurring in the next two years (at least that we observed). Unfortunately, they have returned this past year.

That Stem survives his brief spells of spasms suggests that local sharks are not the ruthless opportunists they are reputed to be. That Stem’s seizures took a two-year hiatus helps me feel more optimistic about his future survival, especially if his young mother is soon to give birth again. If she does, her attention will turn to the newborn. Stem will be on his own.

As always, Capt. John and I wish this little innocent surfer, and his schoolmates, the best of luck.

Follow-up Facts

No one knows much about dolphin seizures at sea.

Surfing is a form of assisted locomotion in which the dolphin rides a wave. In the chapter on surfing in my book, Why Dolphins Jump (available from the DolphinsDigital.org store), I suggest that human snow skiing may be the most similar sensation to dolphin surfing.

We study wild dolphins closely but do not handle them. Thus, we confirm a female’s pregnancy only after she gives birth. It is year-long wait but exciting to accurately predict pregnancy by observing the expectant mother’s behavior at sea.

Bottlenose dolphins are pregnant for a year. This convenient time frame enables us to search the data set of the year before to identify any males in the female’s company as candidates for the calf’s father. We have yet to collect the genetic samples that enable us to verify a calf’s father.

Whoa, Ann! You are amazing! And way past Extra-ordinary! I ordered 5 books! I can’t wait to read all about Why Dolphins Jump! I love the fact that you care enough about us to add pictures to books. A picture is worth 1,000 words - yet when you add the way you know how to play with words… use words to describe --- the book becomes more than 3-D picture. The words become a vision of wonder, full of positive and wonderful and peaceful thoughts. What a world this would be if every person could witness the world through your eyes and read your books. Paradise.

[after receiving her copies of Why Dolphins Jump]...

I hope you are having a peaceful day!

You are INCREDUBLE – Fabulous and inspiring.

The Book “Why Dolphins Jump” is an astounding and way more than I expected. You took your time to explain each 169+ pictures to exactly what they are doing… and I think I have a feeling more about dolphins than many people. I learned how compassionate, intelligent, inquisitive, and playful they are.

The truth is before I ordered the books (5) I was just going to give them to my grandkids, and be on my merry way. However, when the 5 Why Dolphins Jumps arrived and I took a first glance of the pictures I was in awe. I had to change my strategy! We are now during the social distancing time-going to talk about each of the 168 pictures Individually on FaceTime. So three / four a day -> it will take us many weeks to discuss each one. I am LOVING it. I feel close to my grandchildren. My grandchildren use the PIC 20 “bow to entice mother (grandmother) to play.” Or Pic 114 “spyhop to play.

Thank YOU! Ann,

Hollie T